In honor of Canadian Thanksgiving, The Takeout is celebrating the nation’s culinary contributions all week long. We hope you enjoy Canada Week.

Like Detroit, its neighbor across the river, Windsor, Ontario, is known as an auto-producing hub—and the history of the auto industry in Windsor goes back almost as far as it does in the Motor City. When Henry Ford started making cars, he set up a factory in Windsor to get around paying British tariffs, and soon, Ford of Canada was exporting vehicles throughout the British Empire. The automaker maintains a presence in Windsor to this day, as does Fiat Chrysler, whose assembly plant is the city’s largest employer.

And also like Detroit, Windsor has its own style of pizza that rose out of the post–World War II era. In fact, Windsor bills itself as the pizza capital of Canada. While Detroit-style pizza is thick-cut and crispy around the edges, Windsor pizza features a cornmeal-kissed crust, not thin like New York (or, heaven forbid, St. Louis), but not as thick as its neighbor’s.

Windsor-style sauce is sweet yet spicy, but the main factor that distinguishes the pizza is its toppings. Or rather, how they’re all put together. Windsor pizza’s classic fixings are pepperoni and mushrooms. But the mushrooms are canned, and the pepperoni is shaved into matchstick-thin slices. It allows for better distribution across the top of a pizza, but nobody’s sure if that’s the reason it’s done.

“I can’t tell you why they did it, but it’s stayed,” says Dean Litster, an award-winning pizza chef known as Professor Zaaa in Windsor. “I still have the sliced pepperoni for other things, but if someone ordered pizza from us and we put round pepperoni on it, we’d have a problem.”

For 60 years, Windsor residents have been fiercely devoted to their pizza. The chains that started in Detroit—Domino’s and Little Caesar’s—have a presence across the border, but their business pales in comparison to any of the dozen local pizza parlors, each offering some variation of Windsor pizza.

“Windsor style pizza is the only style pizza we make,” says Ralph Mattano, owner of Sam’s Pizzeria and Cantina, which can lay a claim to being Windsor’s oldest Italian restaurant. “We wouldn’t try to push anything else. If it ain’t broke, we’re not going to try to fix it.”

The high point of Italian immigration in the United States was the late 19th and early 20th century, but in Canada, the great migration came in the years following World War II. Those immigrants were drawn, like their compatriots in the United States, to plentiful industrial jobs.

Any city in the United States with a significant Italian population had its own Little Italy, replete with restaurants serving pizzas—or communal ovens that men stoked before leaving for work so their wives could use them for baking.

But the dish really went mainstream following World War II. The New York Times detailed its growing popularity in 1944 in the sort of prose American newspapers used to explain mysterious foreign dishes. A dozen years later, it marveled at pizza’s popularity, noting that immigrants, advertising, and refrigeration “have made pizza as delectable as such other postwar imports as [actress Gina] Lollobrigida,” and speculating if pizza could supplant the hot dog as America’s favorite food.

Italian restaurants started opening in Windsor in the 1940s—Sam’s opened in 1946—and while the origins of Windsor pizza are murky, most accounts point to one place originally located at Wyandotte Street and Victoria Avenue downtown.

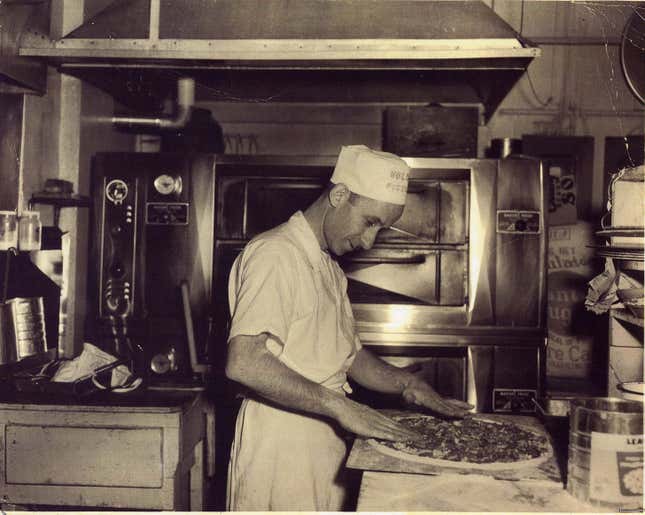

“There are few definitive facts and quite a bit of myth and legends,” says Craig Capacchione, exhibit coordinator for Museum Windsor. “But Volcano Pizzeria is usually seen as the Godfather of Windsor style pizza.”

Volcano had a fleet of iconic delivery vehicles, first Jeeps then Volkswagen Beetles, that crisscrossed the city, and soon Windsorites had acquired a taste for the pizza. Pizza itself was invented out of thrift (it’s said it was originally made so leftover dough insufficient for a loaf of bread wouldn’t go to waste), and the Volcano recipe made do with what was available: specifically, canned mushrooms. Windsor pizza predates the mushroom farms in nearby Essex County, Litster says, but the canned mushrooms also lead to a distinctive taste.

“Fresh mushrooms actually give off water when they’re cooked,” he says. “They can make the crust soggy. It’ll come out like a swamp.”

Soon, people who worked at Volcano left for other restaurants or started their own, bringing the Windsor pizza recipe with them. A lifelong Windsor native, Mattano has eaten Windsor pizza since he was a child nearly 50 years ago. He started his pizza career as a driver for Gavino’s, a now-defunct pizzeria in Windsor, before he and his family bought Sam’s in the 1970s. Sam’s is near the University of Windsor, and students there are no different from anywhere else: Pizza is a staple. “Most of our clientele is university students,” Mattano says. “Pretty much everyone likes it.”

Litster, 34, grew up eating Windsor-style pizza. At 14, he went to work at Armando’s, a pizza restaurant that was founded in 1967. “I started washing pans and folding boxes,” he said. “Now I own my own franchise. I’ve only done one thing in my life and that’s make Windsor pizza.”

Litster loves to experiment with pizza, and started entering pizza-making contests, finishing third at the 2015 Pizza Expo in Las Vegas. “That really put us on the map,” he says. Since then, Armando’s has won first place at the Canadian Pizza Summit, with a new twist: a deep-dish Windsor pizza. The dough ferments for four days and is baked twice, taking elements from both the Sicilian and Detroit styles. (Litster will be giving a demonstration at this year’s virtual summit on October 19.)

“It’s something for the next generation, to complement traditional Windsor-style pizza,” he says.

Today, there are more than a dozen restaurants serving Windsor pizza, and each can probably trace it back to someone who worked at Volcano, Capacchione says. And each has its own loyal customer base.

“If you asked 10 Windsorites the best pizza shop in Windsor you could easily get 10 different answers,” he says. And none of them would be chains.

“The local places have the stronghold,” Litster says. “All the pizza in the area uses the same ingredients. It’s the people that run the stores that make it the customers’ favorite.”