In Los Angeles, the Skirball Cultural Center is currently running an exhibit that showcases the history of the Jewish Deli in America, from its humble food cart origins to its brick-and-mortar temples of smoked, cured meats and brined vegetables. The title of the exhibition, “I’ll Have What She’s Having,” is a reference to the most famous scene from the 1989 film When Harry Met Sally, filmed at the famous Katz’s Delicatessen of Manhattan’s Lower East Side (and indisputably the most famous film scene ever set in an American deli). The exhibit captures delis at their cultural peak in the 20th century, and while the number of delis has waned since then, those that remain continue to be a vital element of major American cities.

The deli was a natural outgrowth of the immigrant experience: move to places where other folks you know already live, then work together to establish your community. These establishments were the nerve center, filling a need as both a place to buy kosher food items and a crucial public gathering space.

It continued to serve those necessary functions following the Holocaust, and more Jewish immigrants arrived in the US. Rena Drexler, who was liberated from Auschwitz and eventually wound up in Los Angeles, opened Drexler’s Deli in 1951. Abe Lebewohl, another survivor who opened 2nd Avenue Delicatessen in New York, “refused to turn away customers for an inability to pay.”

The enduring appeal of the deli is as much about food as it is about simply being surrounded by other people. Some are hungry, some are satisfied. The smell of meat is as visceral as the sounds of old people slurping soup or the frenetic energy of the cashier at the end of the bustling cafeteria line.

I have to give a shoutout here to Manny’s in Chicago, which was one of the many great delis featured in the Skirball exhibit. More specifically, credit is due to Manny’s latke, an absolute unit of a potato pancake and one of those foods I’ll always dream of eating.

How delis became a local news source

One of the most enlightening sections of the exhibit put a spotlight on the trade and union publications for and about delis in 20th-century America. One, the Mogen Dovid Delicatessen Magazine (operated by the Mogen Dovid Delicatessen Owners Association), ran from 1930 to 1939 and “covered local politics, racketeering issues, union matters, and community news.”

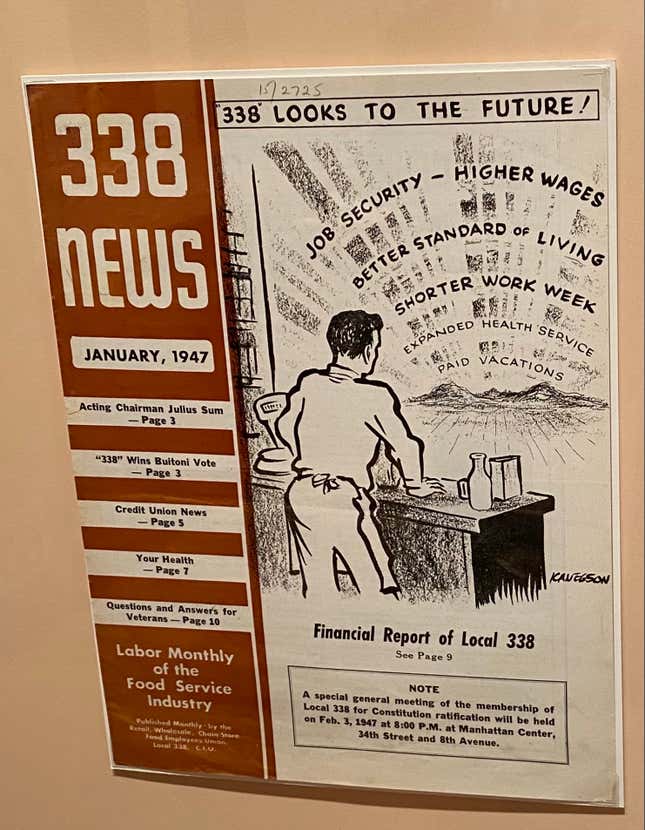

“Labor Monthly of the Food Service Industry,” meanwhile, was a newsletter circulated by New York City’s Local 338, the bagel bakers. The image on the cover hows a weary bageler looking out across the landscape toward a mountainous horizon, beckoned by the sunrise, its rays accompanied by phrases like “job security,” “higher wages,” “shorter work week,” and “expanded health service.”

Local 338, the exhibit explains, was able to secure better wages for its members, but the mass-production of bagels, which became standardized in 1958, “undercut [the unions’] ability to bargain collectively.”

The origins of the hot dog

As Jews arrived in the United States, the country was becoming a beef nation. A hot dog isn’t a deli food, per se, but the two are indirectly linked. In America, the growing abundance of the cattle industry aligned with the technological innovation to process them on a mass scale: Slaughtering and dressing a cow could take eight to ten hours by hand, but by 1890, “industrial packing houses cut that time down to thirty-five minutes.”

Creating an all-beef hot dog that was also kosher was a new development in the sausage world, and it became incredibly popular. Vienna Beef was founded by two Jewish immigrants who sold their dogs at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. The salad on top, “dragged through the garden” as a Chicagoan would say, was in response to the need to give Depression-era customers a bit more bang for their buck.

The Chicago dog is an example of how multiethnic collaboration can produce legendary results. The dog itself was a Jewish creation. The poppyseed Rosen’s roll was the work of a Polish Chicagoan. Tomato and onion for our Italian palates. Sport peppers from Mexico. Influences converging in a dish that embodies an entire city’s cuisine.

The lasting impact of the Jewish deli

Successful delis will always retain a mythical quality. Presidential hopefuls hungry for attention visit them on the campaign trail. There is a great image of Guns N Roses sitting in debauched malaise at a booth at Canter’s Deli in Los Angeles, their first publicity photo as a band. It’s a place you go to get really full, to the point that you start making those noises only someone who has eaten too much can make. It’s a place of sight and sound and smell, a full spectrum of the human eating experience, which is beautiful and ever so slightly disgusting at the same time.

Maybe Art Ginsburg, a Los Angeles deli owner, put it best when he “once jokingly referred to the deli’s huge framed photos of pastrami and corned beef platters as ‘Jewish pornography.’” The main difference is that with pastrami, it’s okay if you finish quickly.